14 Aug Another lens to view British-India relations on Indian Independence Day

Today, as India celebrates 70 years of independence from the British, there is an alternative lens to view the history of the two nations. A history not solely defined by the Raj, but one that evolved during a window in the mid-eighteenth century before British rule became entrenched. I’d go so far to argue that to fully understand 1947, you have to understand how the British entered India in the 1770s.

Back then, when the future wasn’t yet written, there was still a possibility of exchange between cultures. This exchange would not be available when racial stratification and ‘us’ versus ‘them’ polarities became the norm. It was a time of acceptance and rejection, when class, rather than skin colour was often the over-riding factor of difference.

Revisionist historians describe a more integrated culture in the south, particularly in Chennai (formerly Madras), where the European and Indian elites interacted in a lively ‘soiree’ culture. As David Washbrook puts it, ‘Long exposure to European ideas gave rise to many other forms of cross-cultural dialogue — which could be positively evaluated by Europeans themselves, even in the metropolis. Most remarkable here was the great Maratha court at Thanjavur.’

As Dutch, French and English trading companies and merchants competed to outmanoeuvre each other, there was no certainty that Britain would succeed as the dominant power. Every time war broke out between the British and French in Europe, south India became the stage on which this rivalry was played out.

In 1776 Britain lost its American colonies and four years later, Tipu Sultan defeated the armies of the East India Company (EIC) in the Second Mysore War (1780—84). In the words of Natasha Eaton, ‘There was no precedent for direct British rule over non-European peoples, nor were there modern examples of European government in Asia.’

But there were some clear racially-motivated trends as colonial power shifted from commercial to political towards the end of the eighteenth-century. While a large Anglo-Indian (then known as Eurasian) community helped England to consolidate power in the early period, from 1786, Anglo-Indians were excluded from European social life and no longer classed as British subjects, but as ‘natives of India’. This was just one of several markers that indicated the death knell of eclectic cultural borrowing and exchange between the two nations.

It also coincided with the transition from the EIC as a small trading body to what would become the world’s first multi-national corporation. Already, John Company, as it was known, was starting to get a reputation for doing everything it could to maximise profits at the tragic expense of its subjects.

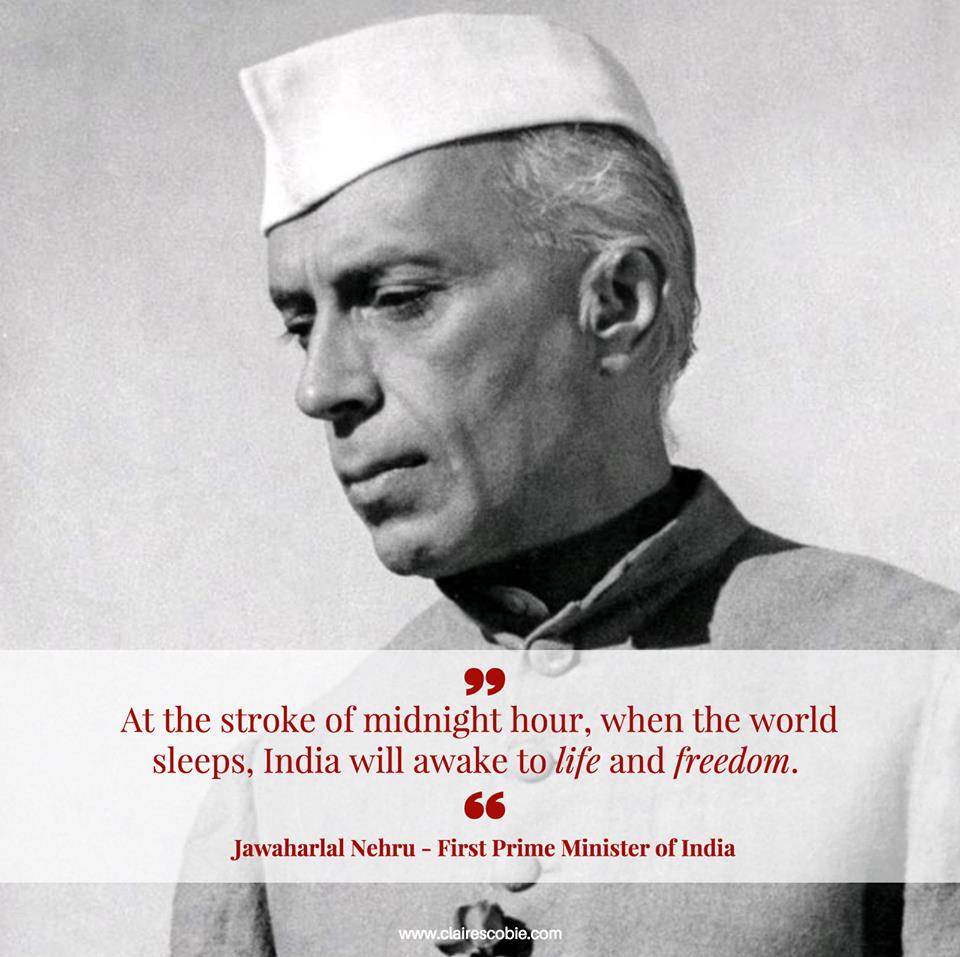

Jawaharlal Nehru, committed nationalist and the first prime minister of independent India (1889 – 1964), noted that around this time the Hindustani word ‘loot’ fell into British vernacular. While more well known for his ‘tryst of destiny’ speech in 1947, Nehru, in The Discovery of India, describes that the process the British would later call trade was in fact ‘plunder’ and that the ‘Pagoda Tree’ — or the tree of money — ‘was shaken again and again till the most terrible famines ravaged Bengal’.

So it’s clear that this pre-Raj period was far from halcyon – surely a nostalgic myth pedalled by those in the entertainment industry – and yet it does offer another perspective. In particular, I would suggest, this time of exchange can be embodied in the little known figure of the dubash — literally translator — a unique Madrasi individual poised at the ‘intercrossing’ between cultures.

From the early 1700s, the dubashes moved from peripheral farming areas of Madras and began to wield influence in the centre as members of the elite. They acted as the interpreter or broker between European Company men, private traders and native merchants, and their early role indicate that the interdependence between the Indian and British may have been on a firmer foundation than was commonly supposed.

While historical research into this subaltern figure is currently in its early stages, one nineteenth-century Tamil text, the Sarva-Deva-Vilasa opens a lens onto the rich artistic life of the city, its indigenous leaders — including several named dubashes — and how both East and West mimicked each other. Just as the English followed the dubashi trend of building garden houses in and around Madras, the dubashes constructed mansions imitating their colonial patrons, developed a taste for Western music and morning horse rides. In the text, it describes how the dubashes rode ‘with numerous hounds and accompanied by English ladies’.

Although this image captures a pivotal moment and the intimacy of relations with the English, the narrator also criticises their foreign overlords and the way in which the colonial state was threatening to destabilise the position of the indigenous elite. There are other figures (such as the banians from Kolkata) who illustrate the complexity of such encounters between East and West, and who also suggest the potential that can occur when multiple relationships and individuals intersect.

So when we join in celebrating with India today — and throughout the rest of this 2017 UK-India year of culture — let us examine our points of connection, of symbiosis and where cultural exchange occurs. By understanding why that can go so wrong — and it did during the Raj, hideously so — we have the chance to re-examine our own shared history in a way that is not nostalgic or airbrushed, but nuanced and one hopes, more authentic.

I would love to hear your thoughts.

Very interesting indeed. Historical honesty is always a good start to addressing issues and healing in the present I very much look forward to reading The Pagoda Tree

Thanks so much Kerry for stopping by. I am glad it struck a chord. Given the areas you work in, there is some potential crossovers? Do hope you enjoy the novel where I explore some of this from a fictional perspective. Claire

Very well stated Claire! Captures the ground realities of the Raj and the complexities of the interrelationships between the rulers and the ruled. Insightful and honest, we need more of this kind of analysis as we move towards a more authentic understanding of histories and communities. Thank you for sharing and look forward to reading your novel. All best. Nirmala

Thanks so much Nirmala, glad you liked the post. So important for me to get this sort of endorsement from a writer and editor like yourself who’ve lived these experiences and know the realities (and complexities) first hand. I feel really buoyed by the response to this piece. So even though I was a bit nervous putting it out there, I will be doing more so. It made me think hard, too, which is always a bonus!

I’m looking forward to reading this book, Claire. I was born in India in early 1950, so just post-Raj, to British parents. My dad managed a paint factory in Mumbai (which was of course still Bombay then) and they were in India from 1946 to December 1954, so they lived through the whole period of partition and Independence. My mother told me of the fear they felt when Gandhi was assassinated, and how relieved they were when they found out it was a Hindu nationalist and not a Muslim, because they were afraid of a civil war. It wasn’t until many years later when I read about the period that I realized quite how privileged my family was. They belonged to a club called the Wodehouse Gymkhana, and they used to go to a swimming pool called Breach Kandy (I think – I was not quite five when we left), and I don’t believe Indians were even allowed in while we were there. Awful in retrospect but Europeans were so very unaware of their privilege at the time.

Jenny what a fascinating story you have – I went once to Breach Kandy – still a Mumbai institution! Have you ever though of writing down your memories? I’d be interested to read them. Hope you enjoy the Pagoda Tree when you get it. Do let me know.